Wheelchair Travel Newsletter: Lyft Access Head Testifies in Federal Court

Testimony from Lyft’s WAV Program Manager raises key questions about Lyft's commitment to accessible service.

This week, I have traveled to White Plains, New York to report on a landmark class action lawsuit, Harriet Lowell et al. v. Lyft, Inc., which is being tried before the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. Lowell and class members contend that rideshare operator Lyft has violated the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL) by refusing to make “Access Mode” available in Westchester County, New York, or anywhere outside of the nine cities where Lyft provides wheelchair accessible service. You can read my pre-trial primer on the case for additional background information.

Though I am a wheelchair user myself and believe rideshare operators are responsible for the disappearance of wheelchair taxis in cities across America, I have approached this case with the intent of offering a fair analysis of the arguments, testimony and, ultimately, the verdict.

Lyft’s WAV Program Manager: “I don’t know”

Yesterday, the court heard opening arguments and plaintiffs called several witnesses, the first of whom was Isabella Gerundio, Lyft’s Program Manager for Wheelchair Accessible Vehicles. Gerundio has held leadership roles at Lyft for nearly five years and, on LinkedIn, describes her responsibilities as directing and overseeing “the product experience, operations, strategy, and finances of all WAV markets in the United States and Canada.”

Gerundio is not a wheelchair user and testified that she had no professional experience in transportation management, the Americans with Disabilities Act, or in developing programs for people with disabilities prior to joining Lyft. Attorneys asked about her commitment to accessibility, and the work she had done (or not done) to expand WAV service in New York and throughout the United States. Testimony and evidence revealed that, under her leadership, Lyft has not expanded WAV service to new markets in the U.S. and the company’s budget for WAV services appears to be decreasing — the 2023 budget was “slightly higher” than 2024, she testified.

When counsel for the plaintiffs pressed Ms. Gerundio on Lyft’s strategy and the basis for her decision-making, her responses were reserved and frequently limited to a single phrase, “I don’t know.” The testimony was unconvincing and a seemingly incredulous Judge Philip M. Halpern rhetorically observed that Ms. Gerundio claimed to have no information about WAV demand, supply or regulation, yet wanted the court to believe that she is committed to expanding WAV services in the United States.

A key question has emerged: What service does Lyft provide?

It now seems to me that a key question before the court, and that the judge has himself encouraged attorneys to address, is whether Lyft’s Access Mode constitutes a distinct service, or if enabling it would simply amount to a modification of the company’s policies, practices, or procedures. That distinction will be important, and it is my view that the judge’s ruling may center on the answer to that question.

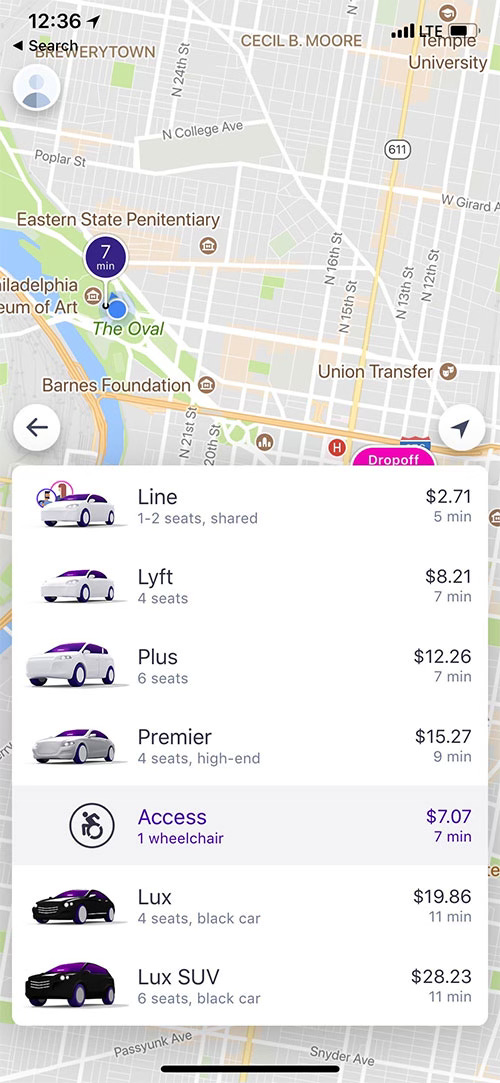

Lyft argues that different vehicle types amount to different services, while plaintiffs argue that enabling access mode is a matter of policy, and that Lyft’s service is connecting riders to drivers, regardless of vehicle type.

Both arguments could prove convincing to the court.

In my view, if we accept Lyft’s longstanding claim that it is a technology company (rather than a transportation company), we could find an interesting parallel in meal delivery services like GrubHub or DoorDash. What service do those companies provide? Does each restaurant listed on their platform amount to a separate service offered by GrubHub, or is it the same service? GrubHub doesn’t source the ingredients, prepare or cook the food, so I think it is fair to say that the company offers a single combined service that is order acceptance/routing and delivery, one that is not distinctly different whether you order a meal from Taco Bell or McDonald’s.

Just as listing a new restaurant would not amount to a new or distinct “service” on GrubHub, opening Access Mode to WAV owners and providers in every city where Lyft operates would not constitute a distinct service provided by Lyft. In fact, nowhere in law is wheelchair accessible transportation described as distinct or separate — only “equivalent,” which is understood as meaning equal, identical, similar, parallel, or analogous, and certainly not distinct, which is understood as meaning different or dissimilar.

If Lyft is a technology company, then its service is connecting riders with drivers — a service that is not fundamentally different regardless of vehicle type. If Lyft instead claims that it is a transportation company, then we should judge it by the ADA’s equivalent service standard — which it would most certainly fail, perhaps even in the 9 cities where the company has already enabled the WAV or “Lyft Access” mode.

Profitability and future law

Judge Halparin quipped that Lyft appears to be in the business of losing money, as the company has never reported an annual net profit.

Yet, in defending the company’s failure to introduce Lyft Access to new markets under her leadership, Ms. Gerundio stated that profitability was a key consideration. She claimed that the company has been unable to develop a profitable WAV strategy, and demurred when questioned about the suitability of plaintiffs’ proposed modifications to policies and procedures, such as the introduction of cross-dispatching for WAVs.

Evidence and testimony revealed that Lyft has only introduced WAV service in cities where they have been required to do so by regulators, or in those that offer significant subsidies. Even in those regions, plaintiffs argue, Lyft has been incentivized to lose money as the company fears the “price of success” — the theory that, if WAV services are profitable and improve access in test cities, more governments will compel the company to provision accessible rides.

More data is needed (and I anticipate will be revealed during this trial) to support or impeach those assertions, but one thing stood out to me — Lyft’s insistence on calculating the financials of the Access mode separately from their standard, electric or luxury modes. This reveals a fundamental problem with existing regulations and, should the court rule in Lyft’s favor, legislators and regulators will need to draft policies that remind business — technology, transportation or otherwise — that accessibility is not optional and is one of the costs of doing business. Equal Access Everywhere must be a requirement for all businesses, even innovators like Lyft that hope to disrupt entrenched industries. 21st century start-ups have failed to incorporate accessibility from the start and are learning that, when accessibility is introduced at a later stage of development, costs are significantly higher. Companies use the high cost of remediation as a defense, but it is one that should be rejected at all levels of government.

What’s next

Over the coming days, I will be in the courtroom listening as the legal teams make their arguments and answer the question, is it reasonable for Lyft to enable access mode everywhere it operates, and does that amount to a reasonable modification as defined by the ADA? Expect more reporting as the trial progresses, along with full analysis of the eventual verdict. If the plaintiffs succeed, rideshare operators may be forced to provide wheelchair accessible rides nationwide. If Lyft mounts a successful defense, disability advocates will know where to focus their attention — lobbying policy makers at the local, state and national levels.

Reporting on stories like this one is a costly endeavor (have you seen hotel prices in New York?), and this newsletter is the only publication providing full coverage from the courtroom. If you would like to continue receiving important accessible travel news, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a one-time or recurring gift via PayPal. Your support drives accountability in the world of accessible travel.

How do we get a message to you or be able to speak to you?